For centuries, humanity has been captivated by the dream of artificial life. Long before the advent of modern robotics and artificial intelligence, this fascination manifested in exquisitely crafted mechanical marvels – automata. Among these, the automaton bird holds a particularly special place, representing a convergence of artistic skill, engineering prowess, and a deep-seated desire to mimic the natural world. This article will explore the history of these fascinating creations, from their earliest precursors to their golden age and beyond, examining the mechanics, the artistry, and the cultural significance of feathered clockwork.

Early Precursors: Ancient Roots of Mechanical Imitation

The impulse to create artificial life isn’t new. Ancient civilizations, particularly in Greece and Egypt, demonstrated an understanding of basic mechanics and a penchant for creating moving statues and devices designed to entertain or honor the gods. While not ‘automata’ in the modern sense, these early creations laid the groundwork. Hero of Alexandria (c. 10 – c. 70 AD), for example, described several ingenious devices in his writings, including self-opening temple doors and mechanical theatrical effects. Although no surviving examples directly resemble birds, the principles of pneumatics, hydraulics, and simple gears used in his inventions were crucial stepping stones.

The Islamic Golden Age (8th – 13th centuries) saw significant advancements in engineering and mathematics, with figures like Al-Jazari (1136 – 1206) creating complex automata, including musical robots and mechanical fountains. Al-Jazari’s Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices details designs for elaborate clocks and automated servants, demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of gearing and control mechanisms. Again, while no extant bird automata from this period survive, the foundational knowledge was being developed and refined.

The Medieval and Renaissance Flowering: Seeds of the Automaton Bird

The medieval period in Europe saw a continuation of mechanical experimentation, often within the context of cathedral clocks. These monumental timekeepers frequently incorporated moving figures, though generally of religious significance rather than mimicking natural creatures. However, the Renaissance, with its renewed interest in classical learning and scientific inquiry, provided a fertile ground for the development of more sophisticated automata. The rediscovery of texts by Hero of Alexandria fueled a new wave of mechanical innovation.

Early Renaissance automata were often integrated into clocks, serving as ‘striking’ figures that marked the hours. These weren’t necessarily realistic representations, but they demonstrated a growing ability to create coordinated movement. The 15th and 16th centuries witnessed the emergence of skilled craftsmen specializing in clockmaking and automaton construction. These artisans, often working for wealthy patrons, began to experiment with more complex mechanisms and lifelike designs. The demand for elaborate and entertaining table clocks and decorative objects spurred innovation.

The 18th Century: The Golden Age of Automaton Birds

The 18th century is widely considered the golden age of automaton birds. This period saw an explosion in their popularity, particularly among the European aristocracy. Several factors contributed to this phenomenon: advancements in precision engineering, the availability of skilled craftsmen, and a growing fascination with natural history and scientific discovery. The Enlightenment emphasized observation and reason, fostering a desire to understand and replicate the wonders of the natural world.

The most celebrated automaton bird makers of this era included the Jaquet-Droz family (Pierre Jaquet-Droz, Henri-Louis Jaquet-Droz, and Élie Jaquet-Droz) in Switzerland, and John Joseph Merlin in England. The Jaquet-Droz family were particularly renowned for their incredibly complex automata, including a ‘Writer’ automaton capable of composing letters and a ‘Musician’ automaton that played the flute. However, their automaton birds were equally impressive. These weren’t simple flapping-wing mechanisms; they sang, moved their heads, pecked at grain, and even displayed remarkably lifelike plumage. The complexity of their internal mechanisms was astonishing, often incorporating hundreds of individually crafted parts.

John Joseph Merlin, a flamboyant showman and inventor, created automata for the British court and wealthy patrons. His creations, though perhaps less refined than those of the Jaquet-Droz family, were nonetheless captivating. Merlin’s automata often featured theatrical displays and incorporated elements of illusion, adding to their entertainment value.

The Mechanics of Flight and Song: How They Worked

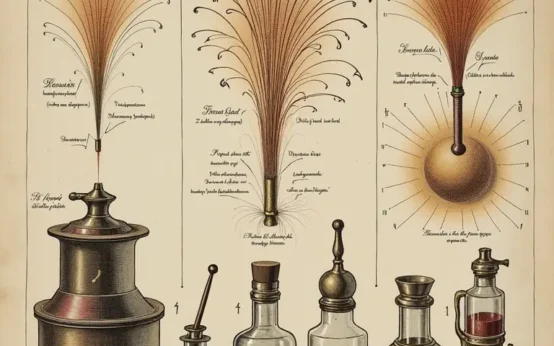

The inner workings of these automaton birds were remarkably intricate. They were powered by a combination of clockwork mechanisms, cams, levers, and springs. A mainspring, wound by a key, provided the energy to drive the automaton. This energy was then regulated and directed by a series of gears and cams. Cams, rotating or sliding pieces with irregular shapes, were crucial for converting rotary motion into the desired linear movements – flapping wings, bobbing heads, and opening beaks.

The synchronization of these movements was a significant challenge. Automaton makers employed sophisticated gear trains and escapements to ensure that the bird’s actions appeared coordinated and lifelike. The singing mechanism was particularly ingenious. Typically, it involved a bellows that forced air across a series of whistles or reeds, creating a melodic sound. The pitch and rhythm of the song were controlled by cams and levers that precisely regulated the airflow. The quality of the sound varied depending on the complexity of the mechanism and the skill of the craftsman. Some birds produced simple chirps, while others could ‘sing’ elaborate melodies.

The feathers themselves were often painstakingly crafted from individual pieces of metal, silk, or even real feathers. These were meticulously attached to the automaton’s frame to create a visually convincing representation of a bird. The attention to detail was extraordinary, with some birds featuring individually articulated wings and tails.

Cultural Significance and Symbolism

Automaton birds weren’t merely mechanical curiosities; they held significant cultural and symbolic meaning. In the 18th century, they were often seen as symbols of wealth, status, and intellectual curiosity. Owning an automaton bird demonstrated one’s appreciation for art, science, and craftsmanship. They were frequently displayed in lavish cabinets of curiosities, alongside other exotic objects and natural history specimens.

The birds also resonated with broader philosophical ideas of the time. The Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and the scientific method led to a desire to understand the mechanisms of nature. Automata, in a sense, were attempts to replicate the complexities of life through mechanical means. They raised questions about the nature of consciousness, the limits of human ingenuity, and the relationship between humans and the natural world. The ability to create something that *appeared* alive, even if it wasn’t, was deeply unsettling and fascinating to many.

Decline and Revival: The 19th and 20th Centuries

The popularity of automaton birds began to decline in the 19th century, as new forms of entertainment emerged and industrialization shifted the focus away from handcrafted objects. The rise of mass production made it difficult for individual artisans to compete. However, interest in automata never completely disappeared. Collectors continued to seek out these mechanical marvels, and museums began to acquire them as historical artifacts.

The latter half of the 20th century and the early 21st century have witnessed a revival of interest in automata, fueled by a growing appreciation for their artistry and historical significance. Contemporary artists and engineers are creating new automata, often using modern materials and technologies, but inspired by the ingenuity of their predecessors. The field of robotics has also drawn inspiration from the principles of automaton design.

The Legacy of Feathered Clockwork

The history of automaton birds is a testament to human creativity, engineering skill, and a timeless fascination with the natural world. These mechanical marvels represent a unique intersection of art, science, and culture. They offer a glimpse into the minds of the artisans who created them and the societies that cherished them. While the technology has evolved dramatically, the underlying impulse to create artificial life remains as strong as ever.

Further exploration into related historical mechanics can be found by investigating the broader history of clockwork toys and automata, offering a wider perspective on the evolution of these mechanical creations. Understanding the intricate workings of these devices also benefits from studying the mechanics of celestial globes, which showcase similar precision engineering. The cultural context of these creations is further illuminated by examining historical culinary secrets and rituals, revealing the societal values reflected in luxury items. To understand the soundscapes these automata would have inhabited, explore the acoustics of historical echo chambers. Finally, considering the broader implications of mechanical replication in a cosmic scale, delve into the history of celestial mechanics.

The Curious Chronicle of Clockwork Toys: Automata, Art, and the Dawn of Play

The Curious Chronicle of Clockwork Toys: Automata, Art, and the Dawn of Play  The Curious Mechanics of Celestial Globes: Mapping the Heavens in Miniature

The Curious Mechanics of Celestial Globes: Mapping the Heavens in Miniature  The Curious Mechanics of Automaton Theatre: A History of Miniature Stages

The Curious Mechanics of Automaton Theatre: A History of Miniature Stages  The Surprisingly Consistent Science of Historical Weather Vanes – Art, Meteorology & Directional Lore

The Surprisingly Consistent Science of Historical Weather Vanes – Art, Meteorology & Directional Lore  The Unexpectedly Consistent Science of Early Firework Composition: Alchemy, Aesthetics & Aerial Displays

The Unexpectedly Consistent Science of Early Firework Composition: Alchemy, Aesthetics & Aerial Displays  The Surprisingly Consistent Logic of Traditional Herbal Remedies: Beyond Folklore, a History of Observation

The Surprisingly Consistent Logic of Traditional Herbal Remedies: Beyond Folklore, a History of Observation