Calligraphy, the art of beautiful writing, often evokes images of monks painstakingly illuminating manuscripts or skilled artists creating elegant invitations. But the story of calligraphy is far more expansive and surprisingly precise than many realize. It’s a journey spanning millennia, continents, and cultures, interwoven with religious practice, political power, artistic innovation, and, ultimately, personal expression. This article delves into the history of calligraphy, tracing its evolution from its ancient origins to its modern manifestations, exploring the tools, techniques, and cultural contexts that have shaped this remarkable art form.

The Dawn of Writing and the Birth of Calligraphy

The very act of writing itself is the precursor to calligraphy. While cave paintings represent early forms of visual communication, true writing emerged in Mesopotamia around 3200 BCE with the Sumerians’ cuneiform. Initially, cuneiform wasn’t beautiful; it was a practical system of recording transactions. However, the scribes who crafted these wedge-shaped marks on clay tablets began to refine their technique, striving for clarity and consistency. This desire for order and legibility laid the foundation for the aesthetic considerations that would define calligraphy.

Around 3000 BCE, Egyptian hieroglyphs developed, a system combining ideograms (pictures representing ideas) and phonograms (pictures representing sounds). The Egyptians held writing in high regard, associating it with the god Thoth, the scribe and keeper of knowledge. Hieroglyphic writing wasn’t just about conveying information; it was a sacred act, and the scribes were highly respected members of society. The precision and artistry required to create these intricate symbols demanded specialized skill and training, marking an early form of calligraphy. The use of reed pens and papyrus, a material made from the papyrus plant, also contributed to the development of distinct writing styles.

Calligraphy in the Ancient World: East Meets West

As writing systems evolved, so did the art of calligraphy. In ancient China, calligraphy flourished from the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE). Initially inscribed on oracle bones – animal bones used for divination – Chinese writing gradually transitioned to bronze inscriptions and then to bamboo and silk. The development of the brush pen, using animal hair and ink made from soot and glue, was crucial. Chinese calligraphy wasn’t simply a method of communication; it was considered one of the highest forms of art, alongside painting, poetry, and music. The ‘Four Treasures of the Study’ – brush, ink, paper, and inkstone – became essential tools and symbols of scholarly pursuit.

The Chinese script, with its complex characters, lent itself beautifully to calligraphic expression. Different styles emerged, including Seal Script (zhuanshu), Clerical Script (lishu), Regular Script (kaishu), Running Script (xingshu), and Cursive Script (caoshu), each with its unique characteristics and aesthetic qualities. Mastery of these styles required years of dedicated practice and a deep understanding of the underlying principles of balance, harmony, and rhythm.

Meanwhile, in ancient Greece and Rome, calligraphy took a different path. The Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet, modifying it to suit their language. Roman calligraphy, particularly during the Imperial period, emphasized clarity and efficiency. The development of Roman capital letters, with their precise forms and elegant proportions, laid the foundation for many of the fonts we use today. Scribes used reed pens and wrote on papyrus and parchment (made from animal skin). While Roman calligraphy wasn’t as overtly artistic as Chinese calligraphy, it was still valued for its legibility and aesthetic appeal.

The Medieval Period: The Flourishing of Western Calligraphy

The fall of the Roman Empire led to a period of disruption in Europe, but calligraphy survived and flourished within the monasteries. Monks dedicated themselves to copying and illuminating manuscripts, preserving classical texts and spreading Christian teachings. This period saw the development of various script styles, including Uncial, Half-Uncial, and Carolingian Minuscule.

Carolingian Minuscule, developed during the reign of Charlemagne in the 8th and 9th centuries, was a particularly significant innovation. It was a clear, legible script that became the standard for book production throughout Europe. It also served as the basis for many modern lowercase letterforms.

As the Middle Ages progressed, Gothic script emerged, characterized by its angular, compressed forms. Gothic calligraphy was widely used in religious texts and legal documents. Illumination, the art of decorating manuscripts with gold, silver, and vibrant colors, became increasingly elaborate. The Book of Kells, a stunning illuminated manuscript created in Ireland around 800 CE, is a prime example of the artistic heights reached during this period. The meticulous detail and symbolic imagery within these manuscripts demonstrate the profound importance placed on the written word.

Islamic Calligraphy: A Divine Art

In the Islamic world, calligraphy holds a particularly revered position. As the Quran, the holy book of Islam, is considered the literal word of God, its beautiful transcription became a religious obligation. Islamic calligraphy isn’t merely a decorative art; it’s a spiritual practice.

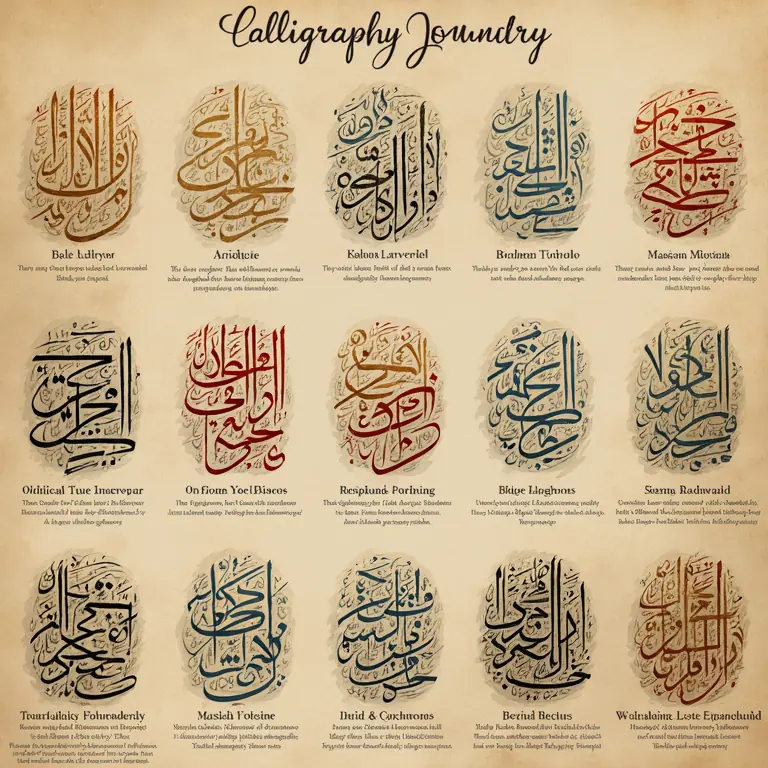

Several distinct styles of Islamic calligraphy developed, including Kufic, Naskh, Thuluth, and Diwani. Kufic, one of the earliest styles, is characterized by its angular, geometric forms. Naskh is a more cursive script that became the standard for everyday writing. Thuluth is a majestic script often used for formal inscriptions. Diwani is a flowing, elegant script developed in the Ottoman Empire.

Islamic calligraphers often incorporate Arabic script into geometric patterns and floral motifs, creating intricate and visually stunning compositions. The art of ta’liq, a uniquely Persian style, is known for its flowing curves and dynamic energy. The use of calligraphy in architecture, ceramics, and textiles further demonstrates its pervasive influence in Islamic culture.

The Renaissance and the Rise of Humanism

The Renaissance witnessed a renewed interest in classical learning and a shift towards humanism. This had a profound impact on calligraphy. Italian humanists sought to revive the elegant Roman scripts of antiquity.

Poggio Bracciolini, a 15th-century Florentine humanist, is credited with rediscovering and popularizing Carolingian Minuscule, which he mistakenly believed to be the script of ancient Rome. This ‘Humanist Minuscule’ became the basis for the italic script, which was characterized by its flowing, cursive forms.

The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-15th century revolutionized book production. Early printers sought to imitate the appearance of handwritten manuscripts, employing skilled calligraphers to design typefaces. The development of typefaces like Roman and Italic played a crucial role in disseminating knowledge and shaping the visual landscape of the Renaissance.

The Modern Era: Calligraphy Adapts and Evolves

The Industrial Revolution and the advent of mass-produced typography led to a decline in the practical use of calligraphy. However, the art form didn’t disappear. Instead, it experienced a revival in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Arts and Crafts movement, led by William Morris, emphasized craftsmanship and a return to traditional skills. Calligraphers like Edward Johnston played a key role in this revival, advocating for a more expressive and individualistic approach to lettering. Johnston’s foundational work, ‘Writing & Illuminating & Lettering,’ published in 1906, remains a seminal text for calligraphers today.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, calligraphy has continued to evolve, embracing new tools, techniques, and styles. Modern calligraphers experiment with a wide range of materials, including watercolors, inks, and acrylics. They also explore unconventional surfaces, such as wood, metal, and glass. The rise of digital calligraphy, using graphic tablets and software, has opened up new possibilities for creative expression.

Today, calligraphy is practiced for a variety of purposes, from creating beautiful wedding invitations and personalized stationery to producing contemporary art and typographic designs. It’s a testament to the enduring power of the written word and the human desire to create beauty.

The Connection to Other Arts

Calligraphy doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s deeply connected to other artistic disciplines. Consider the parallels between calligraphy and traditional folk music scales, both rely on established structures and variations within those structures to create beauty and expressiveness. The balance and flow inherent in calligraphy also find echoes in the visual arts, particularly in abstract expressionism and minimalist design. The principles of composition, rhythm, and harmony that govern calligraphy also apply to other art forms.

Furthermore, the history of calligraphy is often intertwined with storytelling and cultural traditions. Similar to the history of shadow puppetry, calligraphy has been used to transmit narratives and preserve cultural heritage. The visual symbolism embedded within calligraphic forms can convey deeper meanings and cultural values.

The Psychology of Beautiful Writing

Why are we drawn to beautiful handwriting and calligraphy? The answer may lie in the way our brains process visual information. Studies suggest that aesthetically pleasing forms activate reward centers in the brain, eliciting a sense of pleasure and satisfaction. The precision and artistry involved in calligraphy can also be seen as a demonstration of skill and dedication, qualities that we admire and appreciate.

The act of creating calligraphy can also be a meditative practice, requiring focus, concentration, and a sense of flow. It’s a way to slow down, connect with the present moment, and express oneself creatively. Interestingly, the appeal of carefully crafted objects and systems also links to our fascination with antique keys and locks, where detail and precision are paramount.

The Future of Calligraphy

While calligraphy may not be as essential for everyday communication as it once was, its artistic and cultural significance remains undiminished. The emergence of digital tools has opened up new avenues for exploration and experimentation, allowing calligraphers to push the boundaries of the art form.

The ongoing interest in handcraftsmanship and the desire for authentic, personalized experiences suggest that calligraphy will continue to thrive in the years to come. It’s a timeless art form that connects us to our past, enriches our present, and inspires our future. Just as humor relies on shared understanding, as explored in the universal grammar of jokes, calligraphy relies on a shared understanding of form and aesthetics.

Furthermore, the subtle but significant symbolism found in various cultural practices, such as the symbolism of knots, demonstrates a universal human tendency to imbue objects and forms with meaning – a tendency deeply ingrained in the practice of calligraphy.

The Curious Science of Automaton Portraits: Likeness, Legacy, and Lost Art

The Curious Science of Automaton Portraits: Likeness, Legacy, and Lost Art  The Curious Chemistry of Lost Colors: Pigments, History, and the Art of Remembrance

The Curious Chemistry of Lost Colors: Pigments, History, and the Art of Remembrance  The Surprisingly Consistent Science of Historical Dye Recipes: From Ancient Textiles to Modern Pigments

The Surprisingly Consistent Science of Historical Dye Recipes: From Ancient Textiles to Modern Pigments  The Unexpectedly Consistent Science of Penmanship Styles: A History of Flourishes, Form & Legibility

The Unexpectedly Consistent Science of Penmanship Styles: A History of Flourishes, Form & Legibility  The Unexpectedly Political History of Fonts: Typefaces & Power

The Unexpectedly Political History of Fonts: Typefaces & Power